The creation of a movement is an effort to give wider audiences an experience they have never been a part of before. This was the crux of the Dogme 95 movement brought on by Thomas Vinterberg and Lars Von Trier in 1995. Brought on by an exhaustion of the studio system and a technological era of filmmaking. Vinterberg and Von Trier along with their Dogme Brethren created a manifesto of thirty films that abides by the “10 Rules of Chastity” (Von Trier and Vinterberg, 1995.). This is where Von Trier’s 2003 film Dogvillecomes into play. A film that was made during the period of the Dogme movement, despite not being a film in the manifesto. Despite not being one of the films, it utilizes many points from the Vow of Chastity while also focusing itself being a debate of realist filmmaking vs formalistic filmmaking and a story based in reality. Realism comes into play while the filmmakers create a story as an allegory for American values and culture.

Lars Von Trier and Tomas Vinterberg attempted to circumvent the notion of film movement in 1995. They spent a short amount of time fleshing out an idea to create a new sense of pure filmmaking. They looked at movements through the ages such as German Expressionism, Italian Neorealism and French New Wave and decided to plant a firm hold on a modern interpretation of a movement. Over the course of a ten-year period, filmmakers from around the world created films for Von Trier and Vinterberg’s manifesto of Dogme. According to the initial layout of the manifesto, there are certain constraints to determine whether a film is to be considered as a Dogme film. Von Trier and Vinterberg wrote out a list of ten rules to be known as “The Vow of Chastity”.

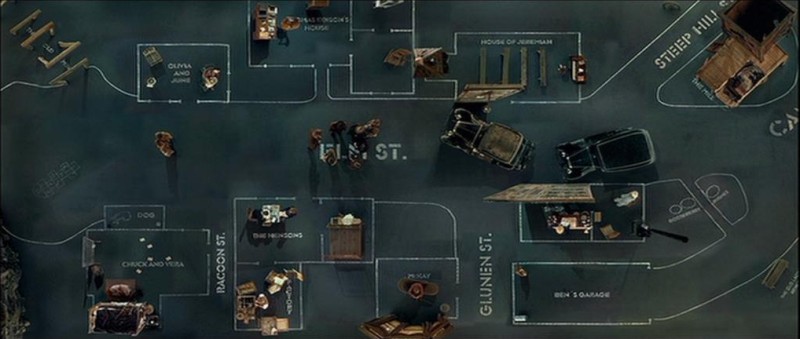

In 2003, Lars Von Trier created a film called Dogville. The Dogme movement was still together and strong but Von Trier did not advocate to have this film featured in his manifesto. The film is intriguing due to its abundance of laws followed by The Vow of Chastity. The film follows the daily happenings in a small, former American mining town in the Rocky Mountains called Dogville. From the beginning of the film, we are greeted by a narration that guides us along the runtime of the film. The first lines we hear is the narrator saying, “This is the sad tale of the township of Dogville.”. From that moment on we are transported into a soundstage, laid out with chalk outlines of buildings, roads and all forms of set aside from furniture and props.  This leads into how the film follows the first rule from The Vow of Chastity. The rule reads “Shooting Must be done on Location. Props and sets must not be brought in (if a particular prop is necessary for the story, a location must be chosen where this prop is to be found)” (Von Trier and Vinterberg, 1995.). In the situation of Dogville, they use the minimalistic set and props to ride the line of this rule. They create the universe of the film by having the characters interact with the setting as if they are in the small town. They implore tactics similar to that of mime and theatre of the absurd by using these small sets to allow the actors to treat the setting as the true atmosphere around them. This tactic used by Von Trier during filming purposefully rides the line between filming on location and not. This is a tactic that toes the line of creating a formalist and realist production. Hugo Münsterberg would have disagreed with this interpretation as in his work The Photoplay: A Psychological Study he would have disagreed with the interpretation of the film with “imitation of nature.” (Singer, 1998). Irving Singer refers to Munsterberg’s writings many times in his book Reality Transformed: Film as Meaning and Technique. Singer even refers to Münsterberg’s arguments as when you see him even bring up the parallels between the stage-play and film when they explore the use of flashback. Seemingly showing a more realistic story in the process. If I can refer back to the use of the narrator’s tone at the beginning of the film, as he refers to Dogville (the town) in the past tense. It shows that the entirety of the film is itself a flashback to an unseen event that we won’t be shown its true nature until the very end of the film. This is what Von Trier was alluding too as he was also shooting the film as if it was created as a stage-play along with his use of flashback to set up the story to be told.

This leads into how the film follows the first rule from The Vow of Chastity. The rule reads “Shooting Must be done on Location. Props and sets must not be brought in (if a particular prop is necessary for the story, a location must be chosen where this prop is to be found)” (Von Trier and Vinterberg, 1995.). In the situation of Dogville, they use the minimalistic set and props to ride the line of this rule. They create the universe of the film by having the characters interact with the setting as if they are in the small town. They implore tactics similar to that of mime and theatre of the absurd by using these small sets to allow the actors to treat the setting as the true atmosphere around them. This tactic used by Von Trier during filming purposefully rides the line between filming on location and not. This is a tactic that toes the line of creating a formalist and realist production. Hugo Münsterberg would have disagreed with this interpretation as in his work The Photoplay: A Psychological Study he would have disagreed with the interpretation of the film with “imitation of nature.” (Singer, 1998). Irving Singer refers to Munsterberg’s writings many times in his book Reality Transformed: Film as Meaning and Technique. Singer even refers to Münsterberg’s arguments as when you see him even bring up the parallels between the stage-play and film when they explore the use of flashback. Seemingly showing a more realistic story in the process. If I can refer back to the use of the narrator’s tone at the beginning of the film, as he refers to Dogville (the town) in the past tense. It shows that the entirety of the film is itself a flashback to an unseen event that we won’t be shown its true nature until the very end of the film. This is what Von Trier was alluding too as he was also shooting the film as if it was created as a stage-play along with his use of flashback to set up the story to be told.

Lars Von Trier is a director that truly knows how to shoot visceral movies. I refer to when a director can create a sense of either discomfort, dread or suspense in the way either himself or his cinematographer shoot the scene. This ideology of creating a visceral movie is also put into the Vow of Chastity. The third rule of the Vow of Chastity is permitting the filmmakers to only use a hand-held camera. This slight movement of the camera on the screen can elevate the level of discomfort of a scene based on its unnatural ability to move in the frame. Think of films such as those from acclaimed director Paul Greengrass and how he films action to attain this sense of visceral filmmaking. Von Trier does this specifically during scenes that involve looking into characters conversations. When he films shot-reverse-shot dialogue sequences you notice as an audience member this shaky aesthetic to the film. This adds to the unsettling nature of the film and is a testament to Von Trier’s ability to create an unnerving tone in all of his filmographies.

The final immediate acceptance of the Vow of Chastity that Von Trier utilizes is the film’s genre. The Vow specifically mentions that films cannot be seen as “Genre Movies” (Von Trier and Vinterberg, 1995). Meaning genres that were mainly overly-produced Hollywood genres, such as sci-fi, action or horror wouldn’t be accepted. Dogville could be seen as a historical drama but seeing as how focused it is on capturing a realistic depiction of life in small-town rural America, it wouldn’t be considered as genre-defining compared to films with bigger productions. Which is what Von Trier and Vinterberg are attempting to do with this movement. To circumvent the idea of over-produced digital cinema and trying to return to the roots of the film by creating these barriers for artists to have to pass in order to create said art.

The question being posed is whether Dogville is a commentary on the redundancy of the realist versus formalist debate as a whole. There are many ways that the film adds to the argument that it is slated as a Dogme production, as I mentioned before. However, there are many rules that the Vow of Chastity contains that in a way break rules while also adhering to them at the same time. A prime example of this is the first rule in the Vow of Chastity. The first sentence is referring to how the film must be shot on location. The location of the film is in a small town with buildings and foliage around. But Von Trier circumvents the notion of location by creating this new world on this soundstage. Where the actors interact with buildings, animals and the location itself as if it were there despite its removal for the sake of artistic choice. This is a prime example of how Von Trier can break his own rules of filmmaking that he set out to use. He does this multiple times in regard to Dogville. Including his rule regarding the restrictions to handheld camera. Despite the overarching majority of the film being resting from the ground perspective of the characters. There are a few shots that would have required overhead work. I refer to the shots that scan the town from above. Allowing the audience to see the chalk outlines of the buildings and giving them the chance to read the names of the locations. This gives Von Trier the appearance to have had stood by his rules but with minor infringements that are both subtle but are so different than the rest of the film that there is clearly intended to jar the audience when they see these shots. Simply because the pace of the film tends to rest either on the ground-based hand-held shots or hand-held shots coming from the other side of the town during the beginning of one of the new sequences as an establishing shot. Another point from the Vow of Chastity that Von Trier is playing around with is the rule referring to special lighting. The characters in Dogville interact with the scenery depending on the time of day as the light from the soundstage either changes to white or black showing the time of day. The film uses studio lights and sperate lighting to simulate a realistic environment on the soundstage that the characters would interact with for the benefit of the scene. This breaks the Vow of Chastity due to the use of lighting but when there is lighting other than the main studio lights, the characters will interact with them as if they were acting in a realistic moment and not just the simulated one that Von Trier is experimenting with for Dogville. There is a famous scene from the film where Nicole Kidman’s character Grace is hiding in a pickup truck, attempting to escape the clutches of the town. The sequence includes the use of montage through screen transition tactics such as fades. This scene is a major stand out of the film due to its content and controversial nature due to the sexual act portrayed on screen. In this scene, Von Trier breaks his fifth rule in the Vow of Chastity which speaks of filters and optical work. He uses the fades to show the passage of time and positions the camera in a way that would require digital work because Grace is hiding under a blanket where we wouldn’t see her otherwise. Von Trier breaks this rule so few times in the film that he certainly would break it for this scene due to its content and risqué nature. Making the sequence stand out based on its controversial appeal is something Von Trier has made a portion of his career on. He adds these camera effects and filters in this scene for the purpose of garnering an alternative reaction from what is normal to the film. This shows that he is not abiding by his roots as a Dogme filmmaker for the purpose of including sequences that involve a potentially acclaimed or noteworthy agenda.

One of the rules in the Vow of Chasity that does not pertain to the technical aspects of the film his sixth one. This one talks about the use of superficial action in the film. The inclusion of weapons, murders and over-the-top violence. Von Trier breaks this rule but the way he does it is incredibly stylistic. In the film, there are a few sequences of sex acts and rape. The way that Von Trier shoots these scenes is very subdued compared to the acts that are being depicted on screen. He shoots them with zero nudity while directing his actors to not make over the top movements or reactions. Specifically, from Nicole Kidman. Her reactions are incredibly subtle and the way her character is portrayed in the scene is as if these atrocious acts are being treated lightly. Von Trier is again toeing the line between filming the act of rape as calmly as he can. As a viewer, we know what Von Trier can do with violence on screen. Specifically, with films such as Antichrist and The House that Jack Built where the themes and messages of the films are explored through the use of over-the-top, exploitative violence. Whereas in Dogville he is refusing to include an intensive portrayal of the violence. We see him explore this again in the culmination of the film. Exactly how the opening line addressed the story, we see the tragedy that befell the township of Dogville. The final sequence of the third act reveals the reasoning for Grace being wanted by law enforcement. A few cars show up and appear to be controlled by her father played by James Caan, a noted mob boss. The final sequence is Grace allowing her father to carry out the destruction of Dogville. We as viewers watch as every member of Dogville is gunned down as we watch the town burn. Similar to the previous point about excessive violence, this scene does not have the same essence of a massacre as it would be in the hands of a different director. The way that Von Trier films this sequence is purposely made to appear as if the violence is not occurring on screen. We watch as the members are killed in mass. However, the actors are clearly shooting blanks, there are no close-ups on fountains of blood being spilled and there are no outright shots of gore. These are steps taken by Von Trier seemingly with the intent to mask the true nature of what he is showing. When looking at the Vow of Chastity and its strict mentioning of having no murder or violence on screen we wouldn’t expect to see these two scenes in the movie from how it is being presented. But the way that Von Trier is showing the violence is telling that he is looking to show the ways that one would, in fact, circumvent the rules of cinema and more specifically the rules of his own movement.

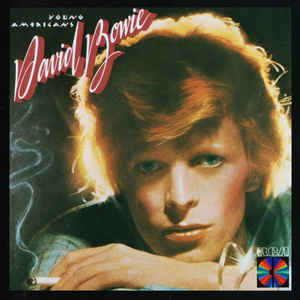

The final portion I would like to address is in regard to the story. The film has been presented as both a film in the style of the realist Dogme movement as well as being a conversation about the movement itself. But the way the story is being told and the themes presented make an argument of it being a realistic story. In Kristen Thompson and David Bordwell’s book on film history, they have a part dedicated to the Dogme 95 movement. They write about how Von Trier “Embraces controversy” and how he made Dogville be an allegory for “American Values” (Thompson and Bordwell, 2018). The first thing that points to this sentiment is the setting. The film takes place in a small and failing mining town. By the time the film’s setting is presumed to be in, mining had been a major industry in the United States. The film depicts how life would transpire in a typical American mining town. They have goods and services for them all to effectively life together sufficiently despite being on their own, close to the mountains. The setting of the film is historically accurate to depict a realistic town, which is what Von Trier would have been looking for to get his point across when constructing his story. This thought displayed in Singer’s book from Münsterberg is a piece of what Von Trier is thinking. Münsterberg talks about the “distinction between appearance and reality” (Singer, 1998). What Dogville does so effectively is that it entices the audience in with its non-conformist presentation by using the unorthodox set. But in reality, it includes this message that many could consider being unpatriotic. This creates that sense of realism that Von Trier wants to add to the story. One of the other moments that show this realistic depiction of America is the credits and the images shown. The images shown in the ending sequence are of poverty-stricken Americans. Many of whom are on the streets, homeless and in compromising positions. These photos include those of children and their poor way of living. These photos are taken from Jacob Holdt’s 1984 documentary book American Pictures. Holdt is known for capturing the reality of culture in his photographs. Being known to have lived amongst the Ku Klux Klan to document their daily lives in the photograph and also his time spent hitchhiking across the United States. These photos are placed in the film to show the true realism behind the eyes of the American populous. In the film, we see the abusive and exploitative nature of individuals when their safety is threatened. Once Grace has a bounty on her and she becomes a wanted woman, the citizens being anxious towards her as they exploit her benefits for their own. This is the sentiment Von Trier is attempting to convey through these photos of Americans that had been held down by the system of the United States throughout their history. The ending sequence is also set to David Bowie’s song Young Americans. The song itself is a commentary on the idea of the American Dream. Talking about how that dream is not attainable for everyone and how it benefits the wealthy before all else. Using time in the song to reference Richard Nixon, race-relations, McCarthyism and capitalism. The song meshes perfectly with the photos to show the realistic poverty divide between Americans and how it can drive a nation apart. Or in the case of Dogville, how it can drive a small town apart. This is the exact thing Von Trier is explaining with his use of these media and ideas in the film. By including the media in the credits, he makes clear his intention to depict this realistic view of American values and change anxiety in communities.

The song itself is a commentary on the idea of the American Dream. Talking about how that dream is not attainable for everyone and how it benefits the wealthy before all else. Using time in the song to reference Richard Nixon, race-relations, McCarthyism and capitalism. The song meshes perfectly with the photos to show the realistic poverty divide between Americans and how it can drive a nation apart. Or in the case of Dogville, how it can drive a small town apart. This is the exact thing Von Trier is explaining with his use of these media and ideas in the film. By including the media in the credits, he makes clear his intention to depict this realistic view of American values and change anxiety in communities.

In short. Dogville is an incredibly deep film that travels through the depths of American ideology in order to create a debate on the realist versus formalist cinematic debate. From his use of the Vow of Chastity to the rule-breaking he explores in order to toe the line to get reactions, he makes a poignant film that has extensive commentary on the history of American values. In 2005 the Dogme 95 movement ended and disbanded. They left behind an extensive manifesto of 30 films that they assume to be cinema at its most base form, depicting reality like no other movement had been able to accomplish. But in the end, films like Dogville are able to explore the deeper meaning of Dogme 95 and the theorizing of the film as a whole while maintaining that sense of realism that the movement was attempting to depict from the inception of the manifesto. A formula that holds bearings in reality only incites debate for years to come.

Work Cited

Singer, Irving. Reality Transformed: Film as Meaning and Technique.1sted. MIT Press, 1998.

Pgs. 22-26.

Thompson, Kristin. Bordwell, David. Film History: An Introduction. 4thed. University of

Wisconson-Madison, 2018. Pgs. 694-695

Von Trier, Lars. Vinterberg, Thomas. Technology and Culture, the Film Reader.1sted.

Psychology Press, 2005. Pgs. 87-88.

Nice. Keep it up man.

LikeLike